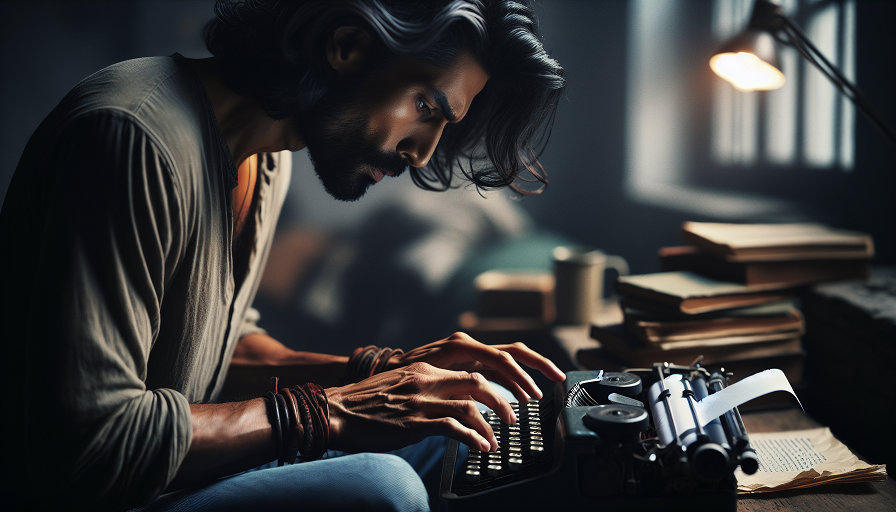

It’s just a mug. Until it’s the one she always used—cracked along the handle, still on the shelf two years after she left. It’s just a coin. Until it’s the one his brother slipped into his hand before the trial. In fiction, objects aren’t just background—they’re carriers. Of memory. Of metaphor. Of meaning that goes unspoken but not unfelt.

Writers often think of physical items as props—set dressing to help flesh out a scene. But when used intentionally, objects can do far more. They become emotional shorthand, narrative anchors, even thematic touchstones that echo throughout a story. They don’t just sit there. They speak.

This article unpacks how to give your objects a voice—not in the magical realism sense, but in the deeply human way that meaning clings to the physical. When readers care about what your characters hold, keep, break, or leave behind, your story gains a gravity that lingers long after the last page.

Contents

Why Objects Matter in Storytelling

We live in a physical world, but we tell emotional stories. The bridge between the two is often an object—something tactile that stands in for the invisible. A photograph doesn’t just show a face. It remembers a life. A ring doesn’t just glitter. It promises—and sometimes betrays.

In fiction, objects give shape to what can’t be easily expressed. They become:

- Emotional containers – holding memory, grief, guilt, or love

- Thematic echoes – representing abstract ideas like time, change, or loss

- Character anchors – revealing values, obsessions, or history

- Narrative pivot points – triggering decisions, flashbacks, or conflict

Used well, they’re not just visual flavor. They’re narrative language.

Turning an Object Into an Emotional Anchor

To make an object emotionally resonant, it must be specific, embedded, and charged. Let’s walk through each step of how to achieve that.

1. Choose the Right Object

Pick something ordinary—but not random. The more mundane the object, the more powerful its transformation can be.

Examples:

- A cassette tape (memory, nostalgia, something that can’t be rewound)

- A scarf (warmth, smell, presence of absence)

- A worn paperback (comfort, legacy, something passed down)

Avoid overly symbolic or dramatic objects unless grounded in character context. A grandfather’s shovel hits harder than a ceremonial sword—because it’s believable. It’s lived-in.

2. Establish the Emotional Bond Early

Don’t wait until the climax to mention the object. Let it appear early—briefly, subtly—so that it becomes familiar. Embed it in routine, memory, or dialogue.

Example:

She always wore that bracelet when she was nervous. Click. Click. The tiny metal charms rattling against the desk as she tapped her fingers.

This early detail may seem small. But by the time the bracelet appears again—perhaps years later, perhaps on someone else—it carries the emotional freight of what came before.

3. Let the Object Interact With Plot

To be more than metaphor, the object must matter to the story. Let it be:

- Something that causes action (a character goes back for it)

- Something that reveals history (found in a drawer, triggering a flashback)

- Something that drives a wedge or forms a bond (two characters argue or connect over it)

Example:

In The Road by Cormac McCarthy, the father’s pistol is both a literal survival tool and an emotional weight. It’s a last resort. A question of mercy. It matters mechanically—but it also speaks to despair, protection, and impossible choices.

4. Echo the Object at Crucial Moments

Repetition builds resonance. Bring the object back at emotional high points—but with change. Let it reflect internal shifts.

Example:

- Early: A photo in a frame on the desk—always straightened, always dusted.

- Midpoint: The photo lies facedown during an argument.

- Climax: The frame is empty. The character carries the photo in their wallet now.

Each reappearance adds narrative layering. The object evolves as the character does.

Thematic Anchoring Through Objects

Beyond emotion, objects can carry theme. If your story explores time, permanence, guilt, or belonging—choose items that naturally reflect those ideas.

Object as Metaphor, Not Symbol

Readers resist objects that feel assigned. But when metaphor emerges from use, the object earns its weight.

Example:

A cracked teacup, carefully glued but no longer usable, can represent attempts at mending the past. You don’t need to say it. Just show her using it anyway—then watch it break again.

Weaving Objects Into Setting

Let the environment reflect thematic motifs through items—not just dialogue or narration.

- A home filled with unlabeled moving boxes (displacement, transition)

- A room where nothing changes—even the dust (grief, stasis)

- A hallway of old shoes, none of which fit (identity, inheritance)

Each item becomes a piece of the world’s thematic argument. It makes the story feel built, not just told.

Characterization Through Objects

How a character interacts with objects reveals who they are more than what they say.

What They Keep

Is it sentimental? Practical? Useless but beloved? People—and characters—form attachments to things for reasons they can’t always articulate.

- Someone keeps broken sunglasses in a drawer. Why?

- Someone wears a jacket two sizes too big. Who gave it to them?

- Someone sleeps with a plush toy, but hides it every morning.

These objects carry story, memory, vulnerability. Let them speak.

What They Notice

What a character observes in a room tells us what matters to them. One character notices the bookshelf. Another, the dusty corners. Another, the absence of photos.

Use object-noticing as a form of interiority. What stands out in the environment reflects the character’s priorities, fears, or longings.

What They Give Away or Leave Behind

Let objects become character decisions. What a character lets go of—intentionally or not—can mark a turning point.

Example:

She walks out without her ring. Not because she forgot it. Because she didn’t.

The object becomes a declaration. Without a single line of dialogue.

Object-Based Story Structures

Some stories revolve almost entirely around a single item. These structures can be powerful when the object serves as an emotional through-line or connective tissue.

1. The Inherited Object

An item passed between characters becomes a bridge across generations or timelines. It might be a weapon, a journal, a recipe book. Each new owner changes—or is changed by—it.

2. The Missing Object

Something is gone. A necklace. A letter. A key. The search for it becomes the plot, but what’s really missing is safety, memory, closure. The object becomes an emotional goal.

3. The Everyday Object That Transforms

A coffee cup. A locket. A pack of cigarettes. Seen again and again—but always in new light. As the story shifts, so does its meaning.

This structure works beautifully in character-driven fiction, where internal evolution matters more than external twists.

Common Pitfalls (and How to Avoid Them)

Not all object usage lands. Here’s where things go off track—and how to fix them:

- Over-symbolizing: If the object’s meaning is spelled out repeatedly, it loses power. Trust the reader to feel it.

- One-and-done: A meaningful object introduced and never mentioned again feels like a missed opportunity. Echo it. Let it evolve.

- Overloading: Too many meaningful objects dilute emotional focus. Choose one or two that resonate deeply.

- Unrealistic attachment: Make sure the emotional bond makes sense. A strong connection needs a memory, a moment, a backstory—even a brief one.

Exercises to Practice Writing Resonant Objects

1. The Object and the Absence

Write a scene in which a character finds an object that once belonged to someone now gone. No flashback. No internal monologue. Let the character’s behavior around the item carry the emotional weight.

2. Object Across Time

Write three short snapshots of the same object in three different time periods in the same character’s life. Let the object’s significance shift in each moment. Track how it reflects emotional change.

3. The Gift

Write a scene where a character gives an object to another—but the object means more to the giver than the receiver realizes. Use subtext, not exposition, to show what’s really being exchanged.

When Things Speak Louder Than Words

In a world saturated with action and dialogue, sometimes it’s the quietest thing in the room that speaks the loudest. A photograph. A watch. A coat hanging by the door that no one has touched in months. Objects don’t narrate, but they carry narrative. They don’t have voices, but they echo all the same.

So the next time your story reaches for meaning, don’t reach for another metaphor. Look to the desk. The drawer. The dusty shelf. Let your characters hold something that holds something else. Because in fiction—as in life—some truths are too heavy to say out loud. That’s why we put them in things.